Water Management Builds Resiliency to Thrive During Weather Extremes

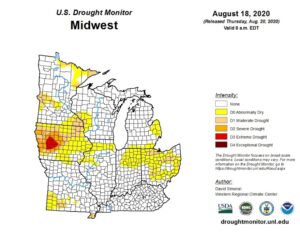

2020 has been, well 2020. Pandemic news aside, agriculture is dealing with another year of weather extremes. I was in the middle of a covid mandated Zoom call when it was cut short by a derecho event striking central Iowa. Fortunately, we came out only losing a few branches and had power back after 12 hours. However, this weather extreme, damaged an estimated 3.57 million acres of corn and 2.5 million acres of soybeans in Iowa. It also devastated Iowa’s 2nd largest city, Cedar Rapids, and many others. Of course, the derecho was not on anyone’s mind in July, but the drought conditions spreading throughout the Midwest have been. As of August 18, the national drought monitor has identified nearly 91 million acres that are experiencing at least abnormally dry conditions with nearly 30 million acres in at least a moderate drought in the Midwest (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University on Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.

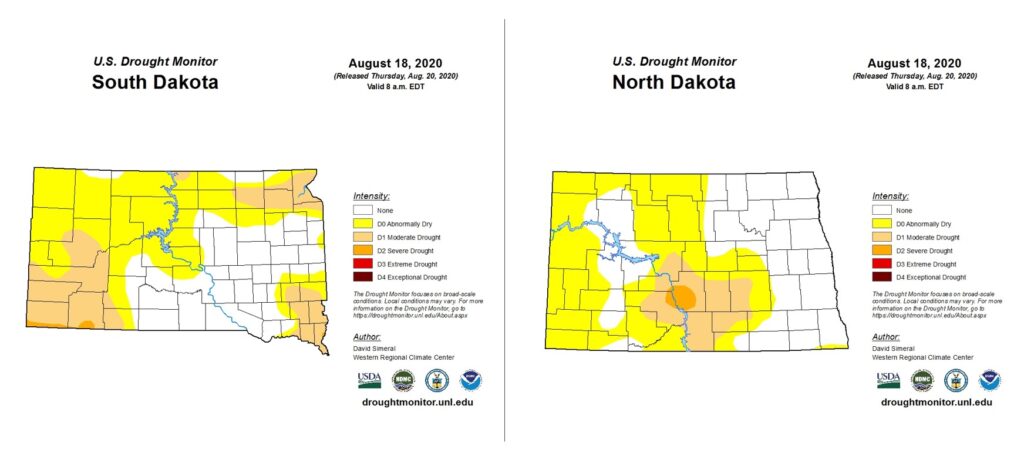

The High Plains states of North Dakota and South Dakota are also experiencing the 2020 drought. They have a combined 16.6 million acres that are categorized as being at least in a moderate drought.

Figure 2 The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University on Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.

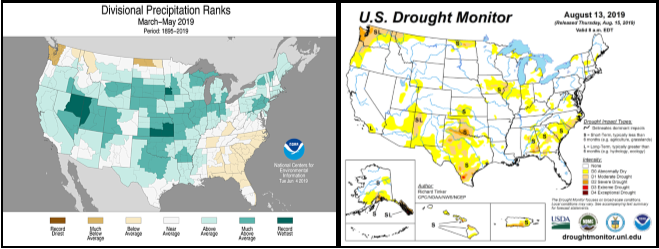

Drought is the extreme that is happening this year. However, that is not always the case. The Midwest consistently deals with excessive precipitation. That is why managing water is the forefront of what ADMC thinks about. Too much or too little water keeps producers up at night, and sometimes both. Last year I wrote about how 2019 was a banner year for drainage water management as a majority of the Cornbelt experienced above average precipitation during the planting season, only to have 52 million acres in Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa register on the August drought monitor when grain should have been filling out. Drainage water management, often referred to as controlled drainage, would have offered the producer the opportunity to drain excessive moisture away in the spring, then to shut off the drains and store moisture in the soil profile for later use.

Figure 3 2019 U.S. spring precipitation followed by extended dry spell.

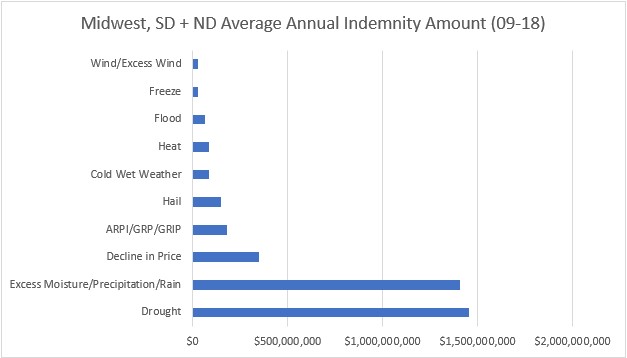

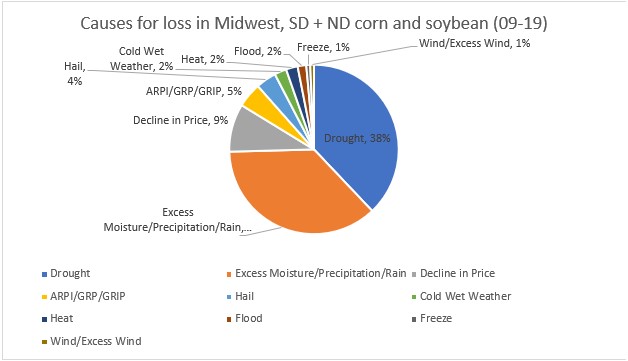

Data from the USDA RMA shows that managing water is one of the most important investments a producer can make as states listed in figures 1 and 2 combine for more than an annual average of $2.8 billion in indemnity amounts due to excessive moisture and droughts. Drought and excessive moisture account for an overwhelming 75% crop insurance reported losses in these areas.

Figure 4 Eight Midwest states + South Dakota and North Dakota average annual corn and soybean indemnity amounts (2009-2018).

Figure 5 Distribution of corn and soybean indemnity amounts in the Midwest + South Dakota and North Dakota (2009-2018).

To better manage for extremes, producers should evaluate the resiliency of their production system. Mother nature is undefeated against simple systems. Building foundational water management systems helps resiliency and profitability. Drainage systems are part of the management needed to convert much of our crop producing areas from what is termed conventional production to soil health building practices such as no-till and cover crops. Many farmers will tell you that in order to make no-till work, you will need a good drainage system in place. Research by Purdue University has shown that cover crops grown on drained plots versus undrained plots added more than four times the amount of biomass. Building soil health adds resiliency by improving infiltration and soil water holding capacity. In addition to improving soil health, producers should also consider subfield profitability. Programs like Profit Zone Manager can identify areas that consistently lose money. Some of these acres can be improved with better drainage infrastructure, others would create better returns by converting to a perennial system. These areas that show to consistently have higher input costs than return can be retired to save money as well as produce environmental benefits like pollinator habitat, carbon storage, and nutrient removal.

Contractors help their customers by recommending improvements in drainage infrastructure to increase production value and limit revenue lost due to excessive moisture, but contractors can take the next step to help to their clients by educating them on the benefits of adding management to their drainage to build resiliency verses a conventional system. Resiliency can be added by taking advantage of the nearly 30 million Midwest acres identified as being suitable for controlled drainage. Controlled drainage works by utilizing a control structure to change the outlet height and allows drainage only when needed. Management zones within a field with slopes <1% are needed to make controlled drainage work. The practice has shown to increase yields by 5-10%, while reducing the amount of nitrogen lost by 48% and phosphorus by 57%. Yield increases can be even more pronounced than the 5-10% in years like 2019 when there is a wet spring followed by a dry summer. To date, management recommendations of the drainage structures have also largely been made with ease of the farmer in mind to prevent negative yield impacts while maximizing nutrient reduction. Now there are cost shareable automated control structures available through the NRCS Conservation Practice Standard 587. Automated control structures can be programmed to allow control of the water table at agronomic optimal levels. This should result in more consistent and larger yield increases.

A subset of the controlled drainage acres can go a step further and utilize subsurface irrigation. Subirrigation works by switching from drainage mode to irrigation mode by pumping water back through the drainage system. Suitability maps for both controlled drainage and sub-irrigation can be found at the transformingdrainage.org website under the tools tab. Like controlled drainage, management zones with flat topography are needed as well as a restrictive soil layer that prevents water loss due to deep seepage. For subirrigation to work economically, there also needs to be enough hydraulic conductivity to allow water to move horizontally from the tile drains which are more narrowly spaced compared to conventional drainage. Transformingdrainage.org rates soils as being suitable for subirrigation if the hydraulic conductivity is >1 ft/day.

In situations where subirrigation is not suitable, a novel drainage water recycling (DWR) system may be utilized. DWR works by pumping drainage water stored in a reservoir to an irrigation system. DWR does work with subirrigation, but it can also utilize center pivot irrigation when soils and topography do not allow for subsurface irrigation. The economics of DWR systems are still being evaluated, but interest is there. Michigan LICA recently hosted a field day in which a 6-acre reservoir will service nearly a 100 acre field.

Crop insurance data and future climate models tell us that 2021 is not going to magically feel any less extreme than 2020. Flipping the calendar should not ease anyone’s mind. Adding resiliency through water management practices which allow soil health practices to thrive and taking advantage of managing our drainage to add the good kind of complexity to our systems should.

ADMC Diamond Members

ADMC Updates

ADMC is now in a position where we are consistently asked to bring the industry’s perspective on how to scale up efforts in a way to ensure future demands will be beneficial to landowners, contractors, and environmental demands. To continue to do so we will need support from our industry members, and we hope you will rejoin. Below are a few of the projects we are currently working on.

- Bringing saturated buffers to scale in the Polk County Saturated Buffer Project

- Installing upwards of 50 saturated buffer sites in Polk County IA in a way that streamlines the process for landowners and makes the practice more attractive to contractors to bid on

- Documenting the process and making it a working model to work in states besides Iowa

- Opening a dialogue with USDA and NRCS to create more demand for drainage water management and the CAP 130 plans

- USDA understands that there are nearly 30 million acres suitable for DWM yet <1% have been implemented to date. ADMC has submitted and received confirmation of delivered letters to under-secretaries Bill Northey (USDA FPAC) and Scott Hutchins (USDA REE) about addressing barriers to adoption and working towards more public/private partnerships to increase adoption

- Working with the Soil and Water Conservation Society and The Nature Conservancy to develop an Edge of Field roadmap to make the economic case, build a capacity to implement, and elevating innovation around structural and water management practices. Similar to what has been done on the soil health initiatives.

- Help to steer the Conservation Drainage Network which brings together university researchers, agency personnel, and industry voices to collaborate on solutions.

- Participiating with the Illinois Sustainable Ag Partnership to complete the 2020 On the Leading Edge: Conservation Drainage Practices for Nutrient Loss Reduction

- Work with ADMC member ISG to put on the Agriculture Drainage + Future of Water Quality Virtual Workshop

Conservation Drainage Events

Share on twitter

Twitter